Recently, we did a little research of our own.

We went through a handful of academic papers and psychological studies, not to make anything sound complicated, but to understand something simple and deeply human: what does “sexy” truly mean for men and women?

And what we found is this: sexy has never really been about appearance.

It’s a state of consciousness, a way of being in your body.

It has two faces: being seen, and feeling seen.

Being Seen

In its outer form, sensuality often starts with visibility: the way we are perceived, desired, or admired.

Yet the way men and women experience this visibility is shaped by psychology, biology, and culture.

Research in social and evolutionary psychology has long shown that men tend to respond more strongly to visual and physical cues of attraction, while women tend to link sensuality with emotional context, trust, and safety (Peplau, 2003; Szymkiewicz, 2024).

This doesn’t mean one group is shallow and the other deep — it simply means that what awakens desire can be encoded differently.

Cultural expectations layer onto this.

Historically, men are taught to look, while women are socialized to be looked at.

Fredrickson and Roberts (1997) call this “objectification”; the learned habit of seeing oneself through the eyes of others.

It explains why women often feel both powerful and vulnerable under attention, and why true confidence rarely comes from being seen alone.

✿To be seen can be beautiful, but only when the gaze is invited, not imposed.

The freedom to choose how we are perceived: that is the first step back to agency.

Feeling Seen

If being seen belongs to the outer world, feeling seen belongs to the inner one.

It’s about how we view ourselves. Our own perception of desirability, competence, and worth.

Psychologists call this sexual esteem: the belief that one is sexually capable, confident, and deserving of pleasure (Amos & McCabe, 2017).

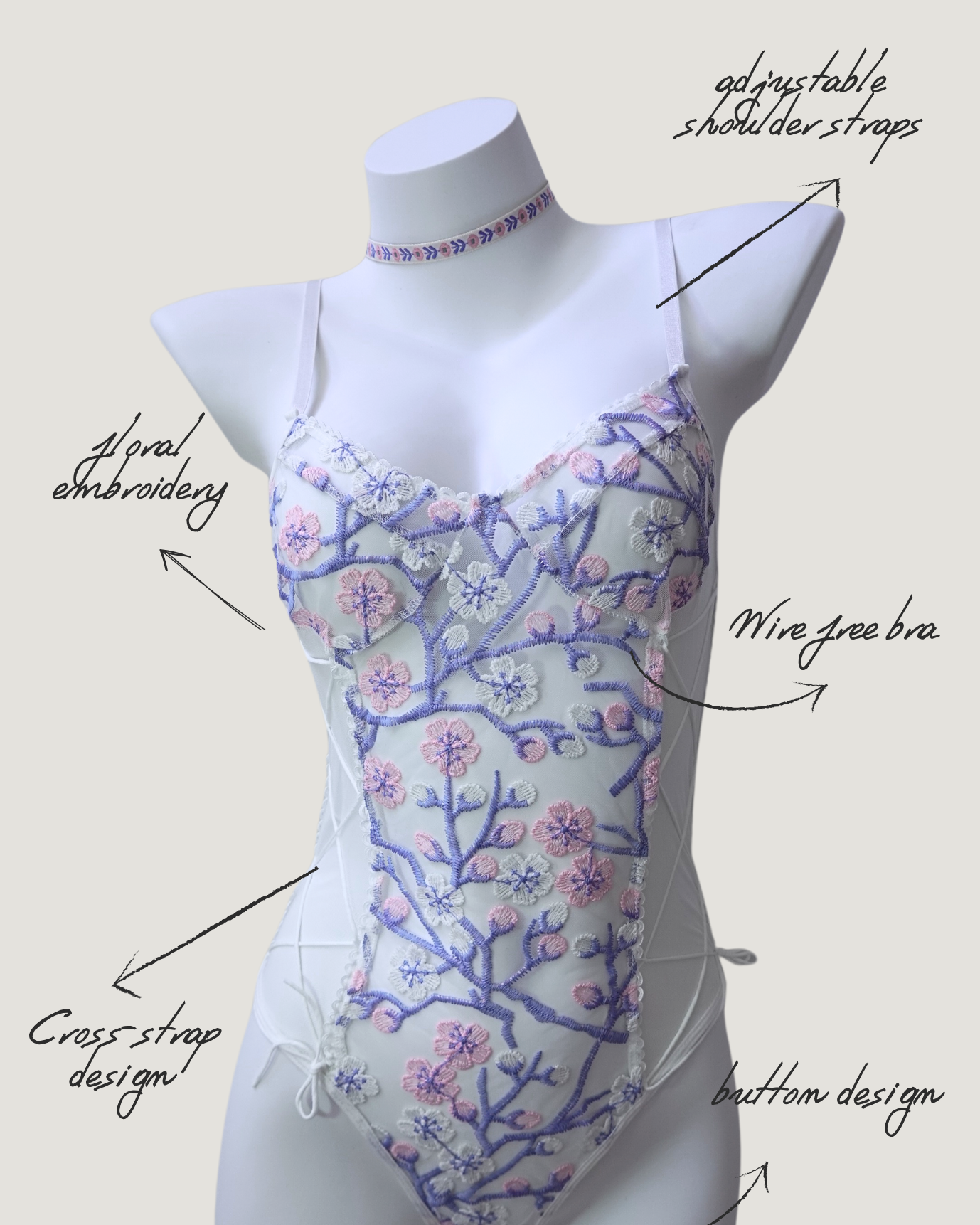

Multiple studies show that a positive body image strongly predicts higher sexual esteem and satisfaction (Shaheen & Batool, 2019).

People who like their appearance, who care for their bodies with kindness, tend to feel more at ease and more expressive in intimacy.

Yet there are nuanced differences:

-

Men often anchor their sensual confidence in an overall sense of capability — strength, presence, the feeling of being physically reliable.

-

Women are more likely to focus on specific aspects of their body or energy, integrating sensuality with emotional connection and self-perception (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997).

These are not fixed truths but reflections of how socialization shapes our relationship with the body.

The essence of feeling sexy is not perfection — it’s self-trust.

Between Self-Love and Being Loved

The deepest pleasure in intimacy rarely comes from performance or appearance.

It comes from that rare balance: when we can admire ourselves, and at the same time, allow ourselves to be admired.

To enjoy being desired does not mean surrendering control.

It means standing so comfortably in your own self-regard that another’s gaze feels like a dialogue, not a demand.

That is the tender science of sensuality — the art of letting appreciation coexist with autonomy.

When we love our bodies enough to let them be seen, and trust enough to let someone see them safely, sensuality shifts from tension to harmony.

It becomes less about proving beauty, more about sharing presence.

Pleasure deepens when both sides of sensuality — self-love and being loved — are allowed to meet.

Closing Thoughts

Sensuality is not a performance; it’s a consciousness.

It starts quietly, in how we inhabit our skin, and expands in how we let ourselves be witnessed.

True sexy doesn’t demand attention, it invites connection.

It’s the calm assurance that says:

I am seen, I am safe, and I still belong to myself.✦₊˚.𖥔 ༉‧₊˚⊹

References

-

Peplau, L. A. (2003). Human Sexuality: How Do Men and Women Differ? UCLA Psychology Department.

-

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. (1997). Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206.

-

Szymkiewicz, M. (2024). Sexual Fantasies of Women and Men – An Evolutionary Perspective: A Review of Research. ResearchGate.

-

Amos, N., & McCabe, M. (2017). The Importance of Feeling Sexually Attractive: Predicting Individuals’ Experience of Their Sexuality. International Journal of Psychology, 52(5), 354–363.

-

Shaheen, S., & Batool, F. (2019). Perceived Physical Attractiveness and Sexual Esteem Among Male and Female Adults. Journal of Psychological Research, 34(3), 565–581.